From figuration to abstraction

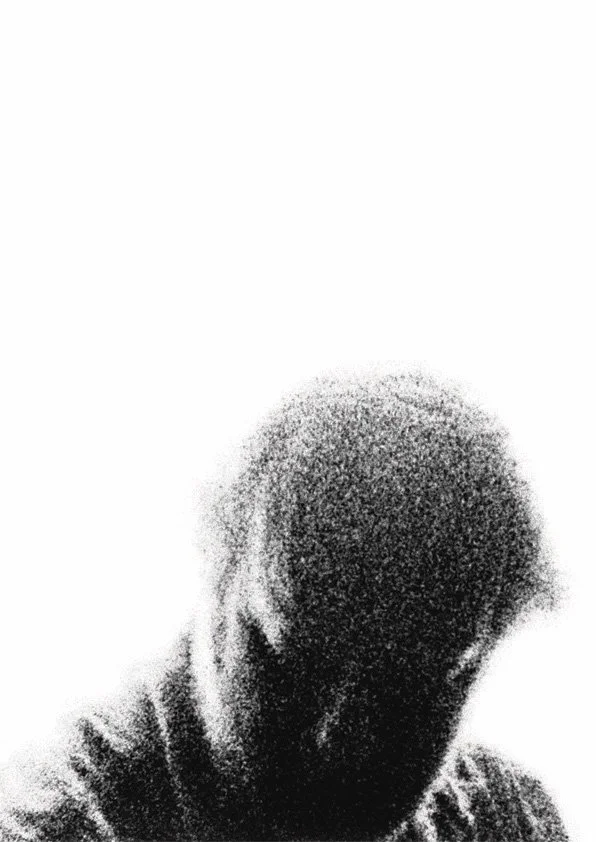

In my third year studying Fine Arts at The University of the Witwatersrand in 1997 I took a series of black and white photographs of my dad around the house. I gave them titles like ‘How to sit’, ‘How to put on a shirt’, ‘How to put on socks’ etc.

How to put on a shirt

How to put on a pair of socks

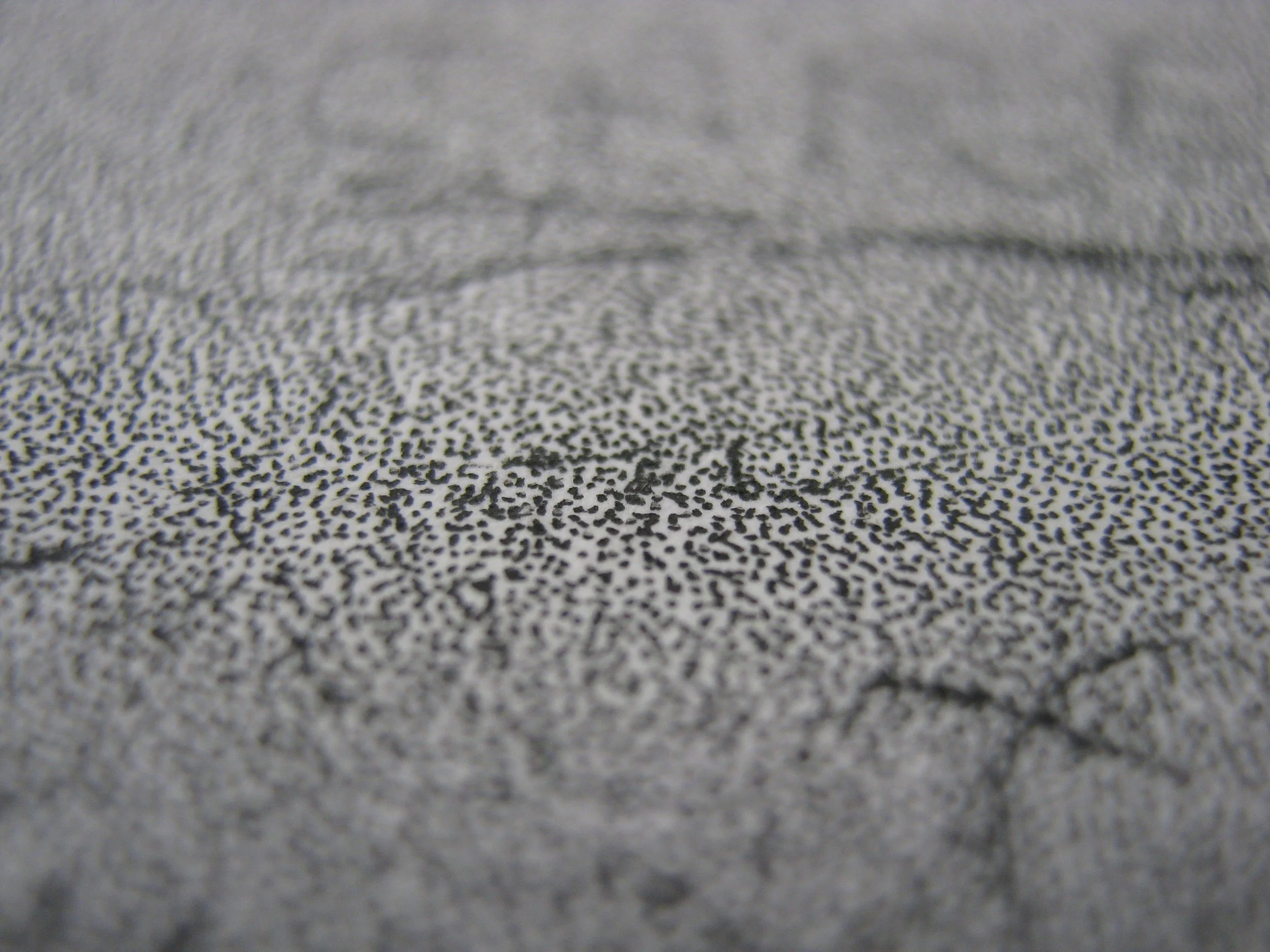

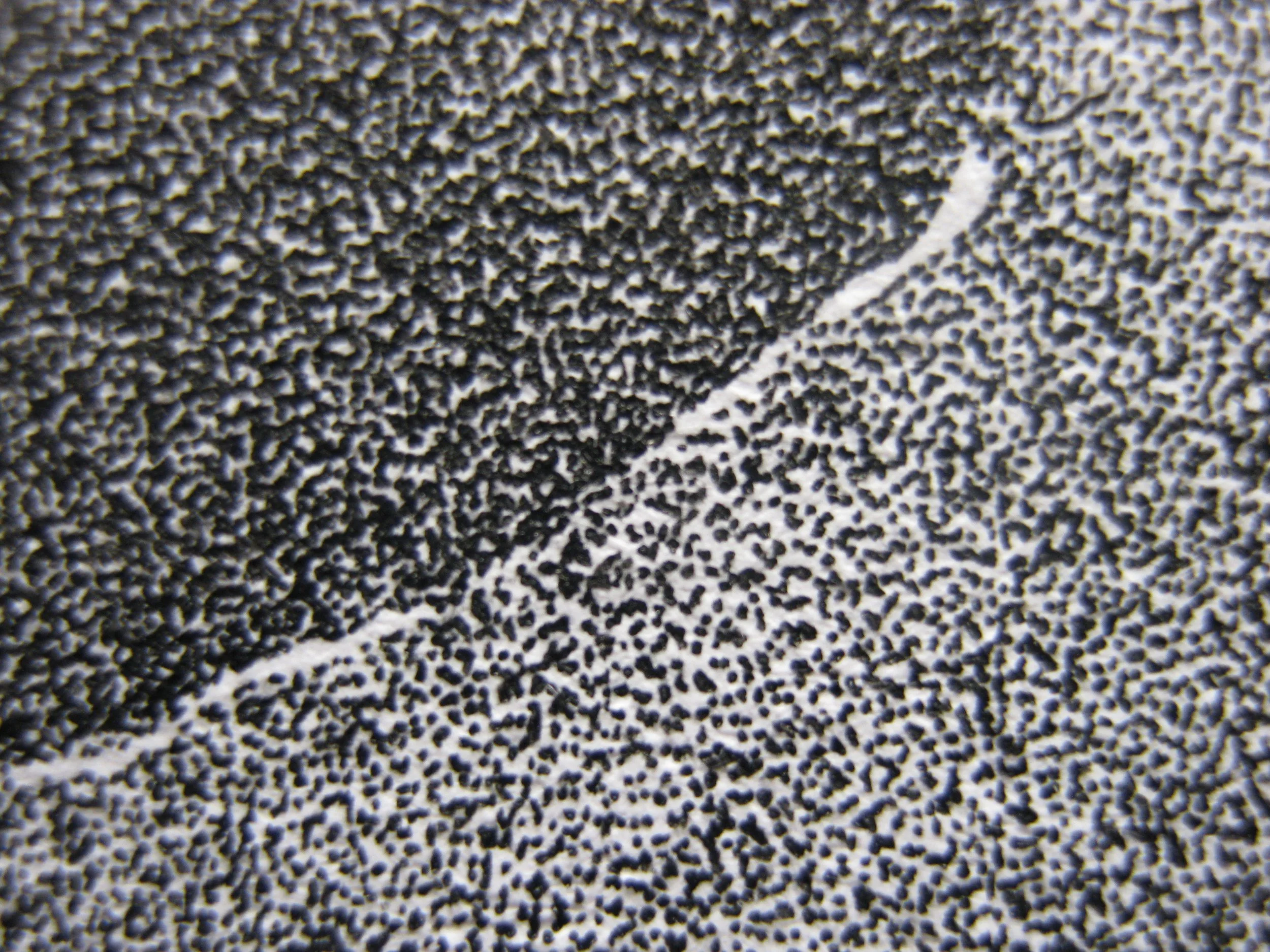

The photographs were taken with extremely fast, grainy film which I processed by hand so I was able to go into the darkroom and explore these images, sometimes finding new compositions and sometimes spending hours looking at the grain of the film and zooming in and out of my father’s neck, his hands, the tilt of his head. Something in those images wouldn’t let go and I was preoccupied with them for over 15 years trying to distil their hold over me.

I wrote the following words in 2006 to remember a conversation I had with my great aunt about her and my grandfather’s immigration from Lithuania to South Africa. She had a thick Yiddish accent, she lived through the pogroms and she fled Europe in 1910. She died a week after I spoke to her:

As she spoke,

her accent,

her tone of voice,

the precise way that her glasses sat on her nose

and her chin nodded slightly above her chest,

the mole above her lip,

the upholstery of the sofa and the texture of my pants

caused time to slip and she was a thousand people.

That slippage of the present was what I was seeing in those images of my father - a tilt of the head that becomes a memory of the future.

From Mirror Aotearoa, 2024

At the heart of the holocaust museum at Yad Vashem, preceded by a dark, spiral corridor, are 6 candles in a pitch black room lined with mirrors. Their reflections are a universe of stars in space, each representing a life lost during the holocaust. Sometimes when my father shifts his weight or combs his beard it is as if he is multiplied like the flame at Yad Vashem so that the palimpsest of his animated form becomes visible. When my father moves, every nuance and articulation of gesture echoes back through generations to his roots in a village in Lithuania. These are the moments and gestures that cause time to slip and he is caught standing between 2 mirrors and the present is a locus from which the past and future radiate.

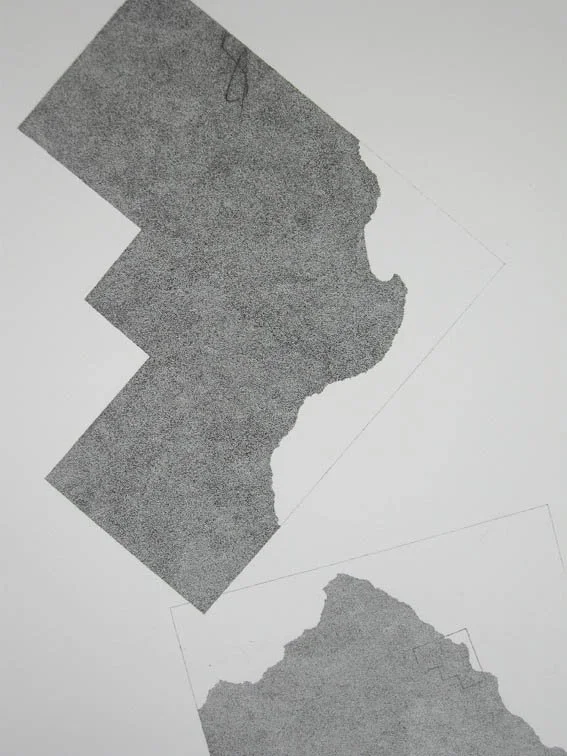

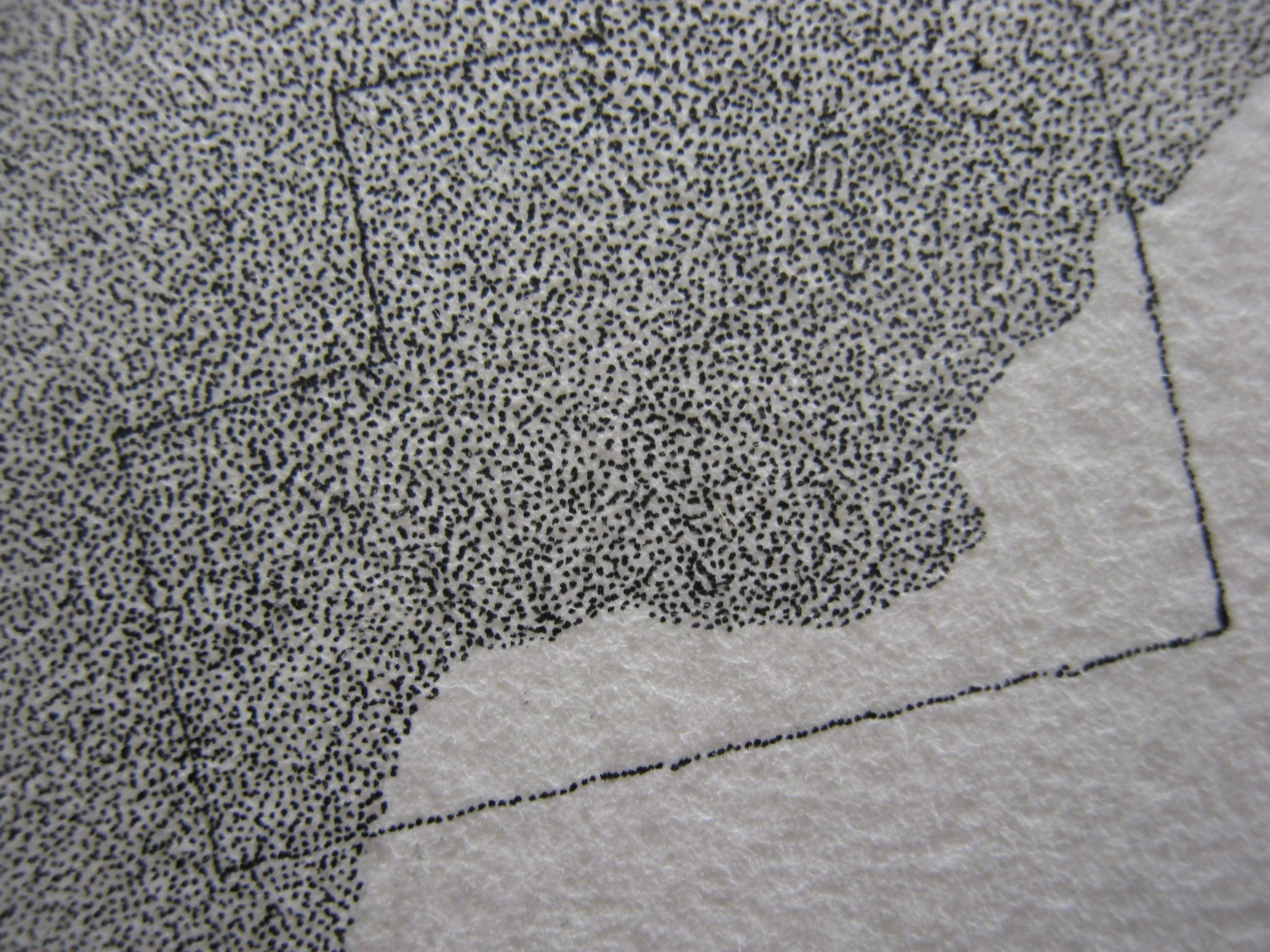

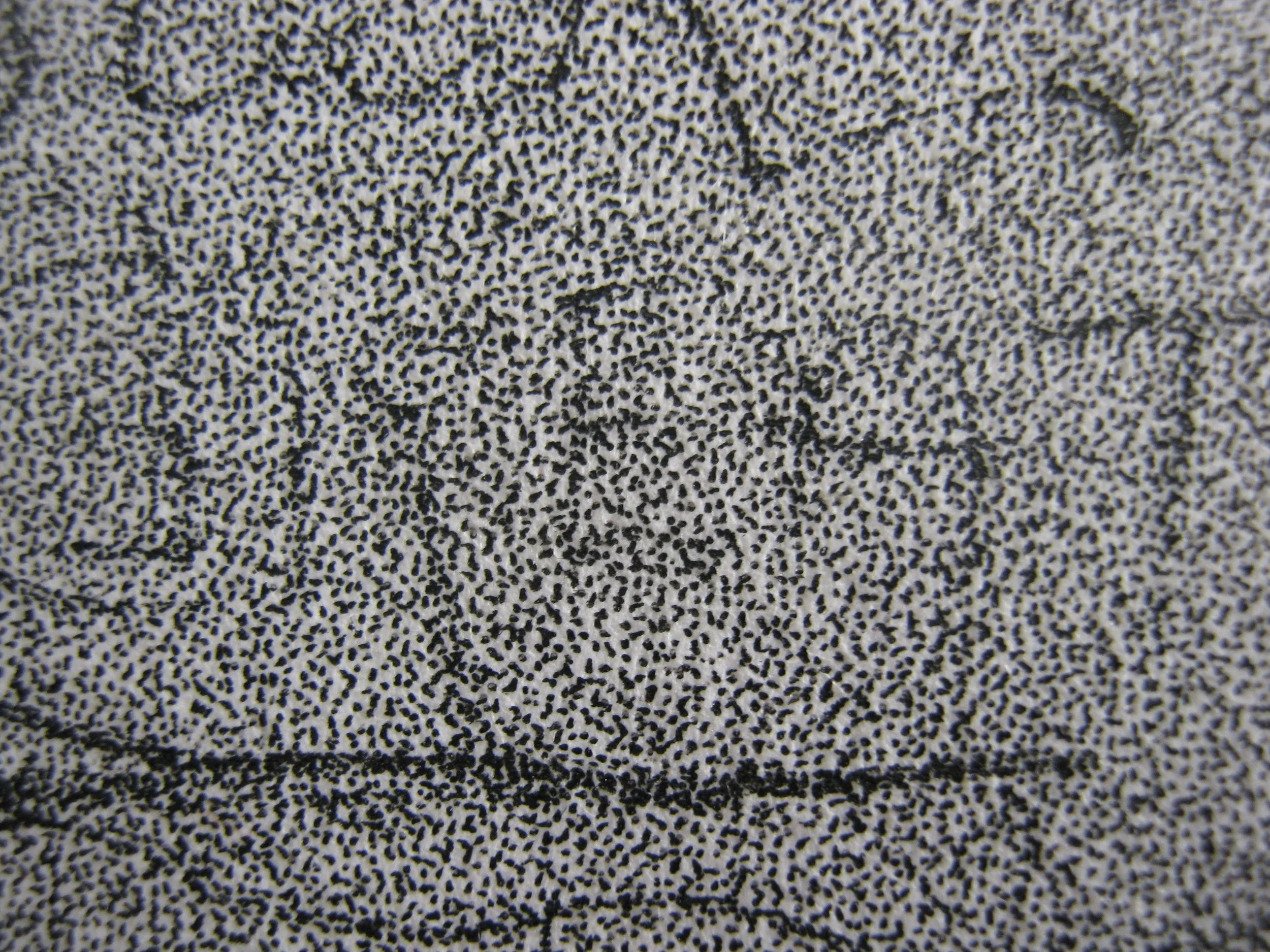

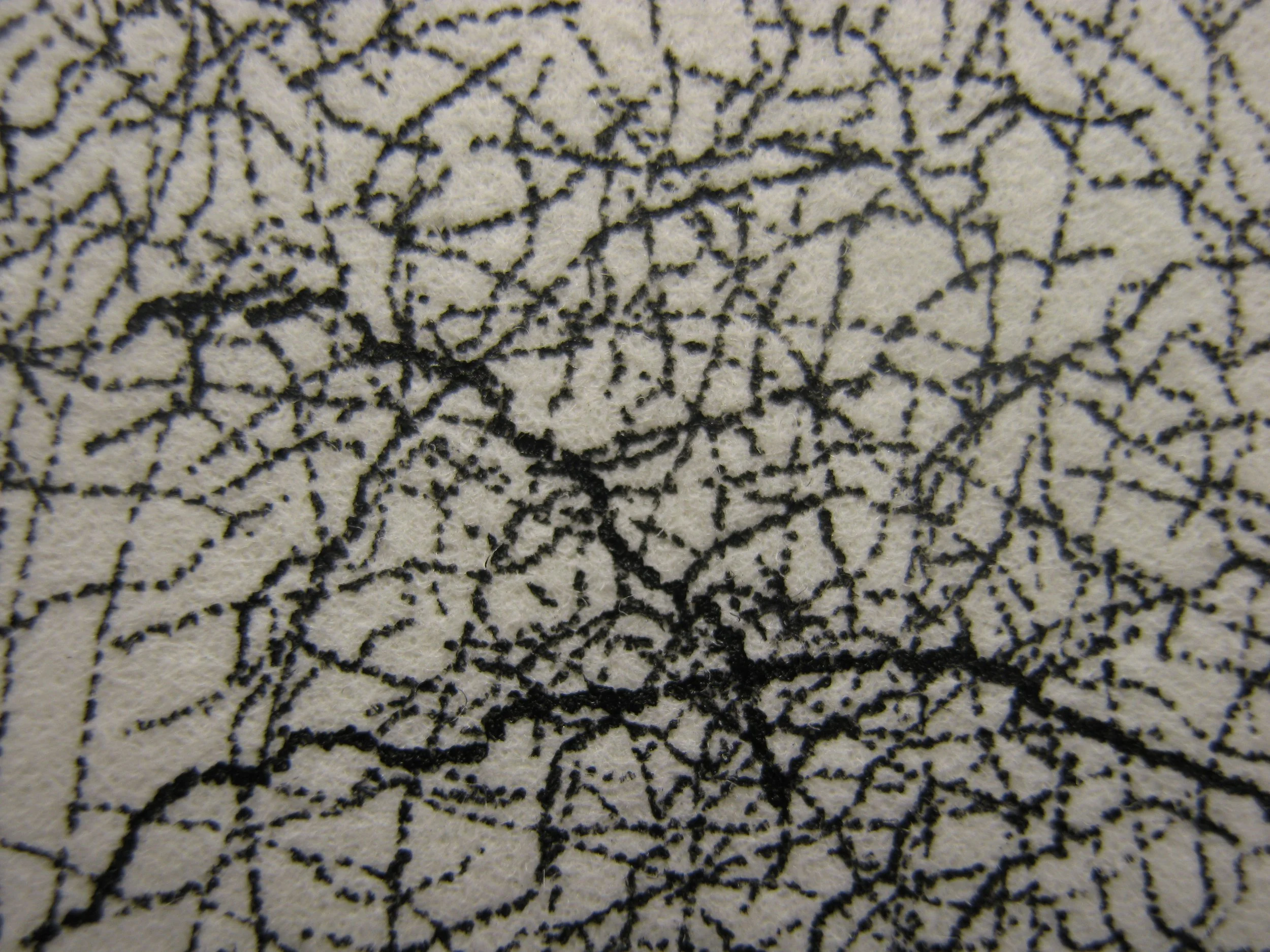

In the darkroom I continued to track in on these images to get closer to an exact moment, a particular line of the tilt of the head that contained the slippage, an attempt to find the border between now and then and soon. In doing so, the grain of the photographs started to take on a kind of genetic significance as well as resembling, in their dispersal of units across a field, galactic images of the far reaches of our universe. The very far and the very large started to come together with notions of the very intimate, close and the very small. Eventually I was left looking at an abstract field of silver halide particles, a field of dots that held both a quantum and a cosmological significance. In trying to grasp it’s meaning the image was obliterated and in its place was something far more universal, something about our place in the universe.