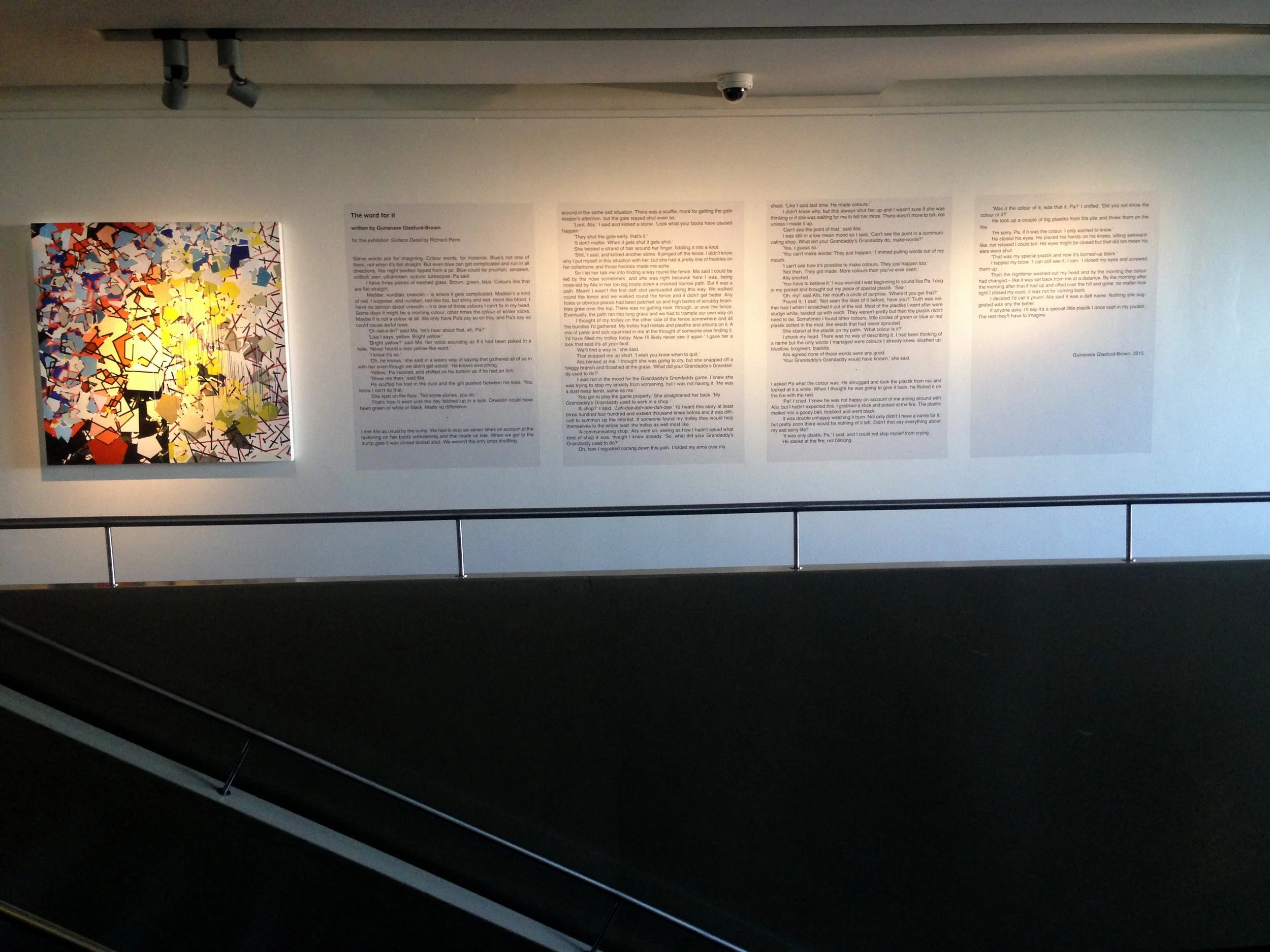

Short story: The word for it

written for the exhibition Surface Detail by Richard Penn

29 October - 26 November 2015

Some words are for imagining. Colour words, for instance. Blue's not one of them, not when it's flat straight. But even blue can get complicated and run in all directions, like night beetles tipped from a jar. Blue could be prushan, seraleen, colbult, sian, ultramreen, ayzure, turkwoyse, Pa said.

I have three pieces of washed glass. Brown, green, blue. Colours like that are flat straight.

Madder, vuridian, oreeolin – is where it gets complicated. Madder's a kind of red, I suppose; and vuridian, red-like too, but shiny and wet, more like blood. I have no opinion about oreeolin – it is one of those colours I can't fix in my head. Some days it might be a morning colour, other times the colour of winter sticks. Maybe it is not a colour at all. We only have Pa's say so on this, and Pa's say so could cause awful rows.

'Or-ree-o-lin?' said Ma, 'let's hear about that, eh, Pa?'

'Like I says, yellow. Bright yellow.'

'Bright yellow?' said Ma, her voice sounding as if it had been poked in a hole. 'Never heard a less yellow-like word.'

'I know it's so.'

'Oh, he knows,' she said in a weary way of saying that gathered all of us in with her even though we didn't get asked. 'He knows everything.'

'Yellow,' Pa insisted, and shifted on his bottom as if he had an itch.

'Show me then,' said Ma.

Pa scuffed his foot in the dust and the grit pushed between his toes. 'You know I can't do that.'

She spat on the floor. 'Tell some stories, you do.'

That's how it went until the day fetched up in a sulk. Oreeolin could have been green or white or black. Made no difference.

*

I met Alis as usual by the sump. We had to stop six seven times on account of the fastening on her boots unfastening and that made us late. When we got to the dump gate it was closed locked shut. We weren't the only ones shuffling around in the same sad situation. There was a scuffle, more for getting the gate keeper's attention, but the gate stayed shut even so.

'Lord, Alis,' I said and kicked a stone. 'Look what your boots have caused happen.'

'They shut the gate early, that's it.'

'It don't matter. When it gets shut it gets shut.'

She twisted a strand of hair around her finger, fiddling it into a knot.

'Shit,' I said, and kicked another stone. It pinged off the fence. I didn't know why I put myself in this situation with her, but she had a pretty line of freckles on her collarbone and those freckles made me ache.

So I let her talk me into finding a way round the fence. Ma said I could be led by the nose sometimes, and she was right because here I was, being nose-led by Alis in her too big boots down a crooked narrow path. But it was a path. Meant I wasn't the first daft idiot persuaded along this way. We walked round the fence and we walked round the fence and it didn't get better. Any holes or obvious places had been patched up and high banks of scrubby brambles grew over the top. There was no getting near, through, or over the fence. Eventually, the path ran into long grass and we had to trample our own way on.

I thought of my trolley on the other side of the fence somewhere and all the bundles I'd gathered. My trolley had metals and plastiks and allsorts on it. A mix of panic and sick squirmed in me at the thought of someone else finding it. 'I'd have filled my trolley today. Now I'll likely never see it again.' I gave her a look that said it's all your fault.

'We'll find a way in,' she said.

That stopped me up short. 'I wish you knew when to quit.'

Alis blinked at me. I thought she was going to cry, but she snapped off a twiggy branch and thrashed at the grass. 'What did your Grandaddy's Grandaddy used to do?'

I was not in the mood for the Grandaddy's Grandaddy game. I knew she was trying to stop my anxiety from worsening, but I was not having it. 'He was a dust-heap ferret, same as me.'

'You got to play the game properly.' She straightened her back. 'My Grandaddy's Grandaddy used to work in a shop.'

'A shop?' I said, 'Lah-dee-dah-dee-dah-dee.' I'd heard this story at least three hundred four hundred and sixteen thousand times before and it was difficult to summon up the interest. If someone found my trolley they would help themselves to the whole load, the trolley as well most like.

'A communicating shop,' Alis went on, seeing as how I hadn't asked what kind of shop it was, though I knew already. 'So, what did your Grandaddy's Grandaddy used to do?'

Oh, how I regretted coming down this path. I folded my arms over my chest. 'Like I said last time. He made colours.'

I didn't know why, but this always shut her up and I wasn't sure if she was thinking or if she was waiting for me to tell her more. There wasn't more to tell, not unless I made it up.

'Can't see the point of that,' said Alis.

I was still in a low mean mood so I said, 'Can't see the point in a communicating shop. What did your Grandaddy's Grandaddy do, make words?'

'Yes. I guess so.'

'You can't make words! They just happen.' I mimed pulling words out of my mouth.

'I can't see how it's possible to make colours. They just happen too.'

'Not then. They got made. More colours than you've ever seen.'

Alis snorted.

'You have to believe it.' I was worried I was beginning to sound like Pa. I dug in my pocket and brought out my piece of special plastik. 'See.'

'Oh, my!' said Alis, her mouth a circle of surprise. 'Where'd you get that?'

'Found it,' I said. 'Not seen the likes of it before, have you?' Truth was neither had I when I scratched it out of the soil. Most of the plastiks I went after were sludge white, twisted up with earth. They weren't pretty but then fire plastik didn't need to be. Sometimes I found other colours, little circles of green or blue or red plastik dotted in the mud, like seeds that had never sprouted.

She stared at the plastik on my palm. 'What colour is it?'

I shook my head. There was no way of describing it. I had been thinking of a name but the only words I managed were colours I already knew, slushed up: bluellow, brogreen, blackite.

Alis agreed none of those words were any good.

'Your Grandaddy's Grandaddy would have known,' she said.

*

I asked Pa what the colour was. He shrugged and took the plastik from me and looked at it a while. When I thought he was going to give it back, he flicked it on the fire with the rest.

'Pa!' I cried. I knew he was not happy on account of me arsing around with Alis, but I hadn't expected this. I grabbed a stick and poked at the fire. The plastik melted into a gooey ball, bubbled and went black.

It was double unhappy watching it burn. Not only didn't I have a name for it, but pretty soon there would be nothing of it left. Didn't that say everything about my sad sorry life?

'It was only plastik, Pa,' I said, and I could not stop myself from crying.

He stared at the fire, not blinking.

'Was it the colour of it, was that it, Pa?' I sniffed. 'Did you not know the colour of it?'

He took up a couple of big plastiks from the pile and threw them on the fire.

'I'm sorry, Pa, if it was the colour. I only wanted to know.'

He closed his eyes. He placed his hands on his knees, sitting awkward-like, not relaxed I could tell. His eyes might be closed but that did not mean his ears were shut.

'That was my special plastik and now it's burned-up black.'

I tapped my brow. 'I can still see it, I can.' I closed my eyes and screwed them up.

Then the nighttime washed-out my head and by the morning the colour had changed – like it was set back from me at a distance. By the morning after the morning after that it had up and offed over the hill and gone; no matter how tight I closed my eyes, it was not for coming back.

I decided I'd call it pruerl. Alis said it was a daft name. Nothing she suggested was any the better.

If anyone asks, I'll say it's a special little plastik I once kept in my pocket. The rest they'll have to imagine.