interview: ceramics nz

Ceramics NZ Vol 6, Issue 1

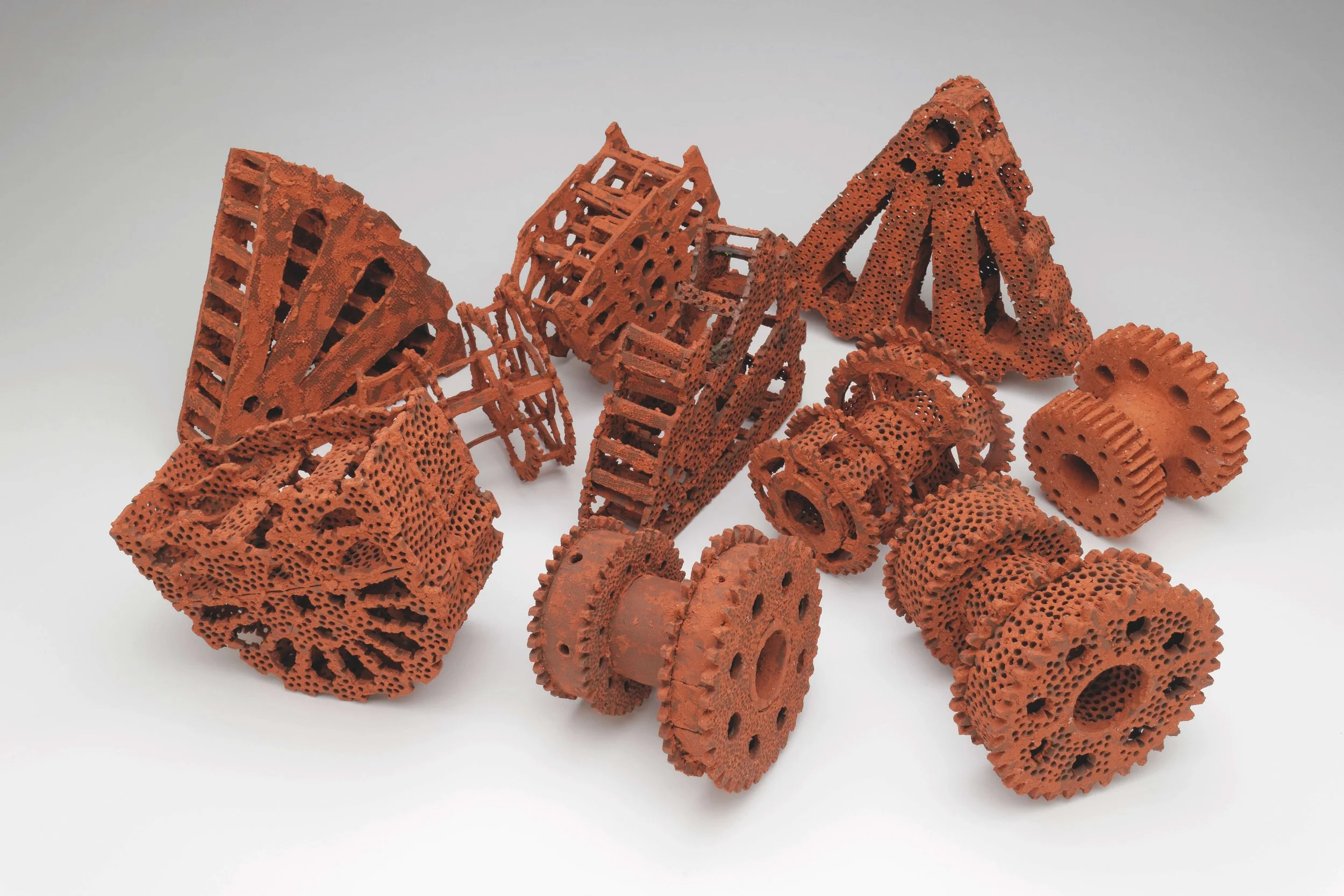

Portage 2022 Premier Award Artefacts - Richard Penn

Interview questions:

When did you begin working in ceramics, and how has your relationship with clay evolved since then?

I completed my bachelors and my masters in fine arts at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2009 and I have been making art and exhibiting ever since. Predominantly I worked in ink, pastel and oil painting but around 2019 I made a few small bronze sculptures that I decided would contrast spectacularly with a shiny orange ceramic base. So it was with these bases in mind that I approached Caroline Schultz Veiera, a potter and teacher who’s studio was a block away from my house in Parkview, Johannesburg. She taught me how to roll a slab and how to join slabs and the rest was trial and error alongside Caroline’s generosity, guidance and knowledge. I never actually completed those bases because like so many artists who reach into the clay bucket, I was immediately hooked and my entire practice became entered around clay. I’m thinking about starting a support group for artists whose practice has been subsumed by the sweet seduction of mud…

Drawing will always be the essential fulcrum of my art practice because it is the most simple and most primal way that I, as an artist can make sense of the world. But the introduction of clay into the studio has changed who I am as an artist in a profound way and I am only just beginning to grapple with it.

The first body of work I made consisted of two splayed slabs joined at the top which I called Totems. The shape of the slabs were designed as a drawing and cut out as a template. I then used the same templates to produce thicker, larger slabs that I stacked on top of one another to produce larger pieces that became known as Artefacts

I tend to move toward complexity in my work so the Artefacts became more and more complex while maintaining their machine-like appearance. I began to think about the interior of these machine parts and wondered what it might look like if I started to strip away surfaces to get a glimpse inside. How much of the form could be eroded before it collapses and becomes incoherent?

Your work Artefacts won the premier Portage award in 2022 – could you please describe the process you worked through in creating these recent objects? In what ways does Artefacts reflect the development of your ceramics practice?

This particular series was developed during a residency at Driving Creek Potteries in the Coromandel in 2022. I found a discarded gear alongside the rail tracks and I took it back to the studio with me. I began by making the gear in Corogold clay. The object’s form reminded me of diatoms and radiolarians but It’s solidity worried me so I began to strip the cog of its solid structure by incrementally reducing it to its supporting walls. It became a game to see how much of the object I could take away while still retaining its structural and aesthetic integrity. The final piece was so basic and so fragile I had to make it directly on the kiln shelf because it was too delicate to handle before bisquing. After completion I could carry the shelf straight to the kiln with the object on it.

Back home in the studio I then applied this process of stripping down a solid form to other artefact shapes I had been working with at the time and the collection of pieces for the Portage Award was the result. This was an incredibly rewarding and important exercise for me and I don’t feel that it is at an end. I see plenty more of these forms in the future.

Your pieces are often highly detailed and structurally complex – Can you tell us about your making and firing processes? What are some material challenges you’ve worked through?

So far I have constructed my work entirely from slabs. Either the slabs are laid directly on top of one another or they are supported by small walls so that the viewer can see its inner structure. All my pieces start out as a two dimensional design and each slab is traced and cut from that design. It’s a little difficult to explain but each slab is slightly different from those above and below it and those differences are marked out on the design in different colours. I suppose its similar to how an architect draws plans for each floor of a building.

Technically, working with slabs is about understanding how your clay dries and by controlling that process. In the more complex, larger pieces I need to cut all the slabs and walls, punch them with holes and store them so they don’t dry out until I have cut and punched all the elements for the entire piece. Then I can begin the construction process which I have to complete as quickly as possible while everything is equally hydrated. I begin that process by treating the slabs and the walls I am joining with a slip mixture I have made using the raw clay from the forests around Driving Creek in the Coromandel. So I have developed quite a regimented process of design, preparation and construction, one that takes into account the changing nature of the material over time.

Almost all my work is fired to Cone 6 and I have reached a size limit with my solid pieces as they tend to crack unhelpfully at a certain scale. This provides an exciting future challenge for me to figure out how to continue to scale up whilst maintaining the structural integrity of the pieces.

What qualities are you looking for in your ceramic works? How do you push these qualities?

There are certain motifs that were once irreverent and bold but that have now lost their power and sit comfortably within the embrace of contemporary ceramics. Work of this kind still tends to take up a lot of the available bandwidth and it’s important to me that I don’t relax into making predictable work. I need to resist pandering to fashionable tastes and continually surprise myself.

I want to make intriguing objects, objects that are different and unpredictable and are embedded with some kind of narrative. I won’t commit to any specific aesthetic because that can and must change over time as my curiosity takes me in different directions. Right now these objects need to look aged and incomplete, their surfaces must be tarnished and rusted and they must look like they are parts of a greater, more complex machine. I like the idea that they are remnants of a lost future civilisation that have been buried underground and travelled back in time to be found in the present.

I achieve this is two ways. The first, as can be seen in the Artefacts from the Portage Prize is to use the Corogold clay as an orange slip which makes for an interesting translation of rust. The second is an extremely high alumina copper glaze which I mixed though trial and error. It is sprayed over the bisqued piece after I have applied a black slip to certain areas. Once it dries I then reapply the black slip to the edges of the piece and fire to completion.

I need to make objects that surprise me. I must be unsure of something when I close the kiln door so that when I open it again there is something unpredictable to discover. I often expect that some of the objects are too fragile for the violence of the kiln and when they crack I love figuring out whether it's a believable crack, an historical crack, a narrative crack. Sometimes it is and the work is improved and sometimes it really isn’t and it’s off to the tip. I also like to provide opportunities for some elements to slump in the kiln by excluding support walls in places. This kind of imperfection tells similar stories of forces imposed on the object over time.

Could you please tell us a little about the behind-the-scenes research and sources of inspiration that inform your practice?

I spend a lot of time thinking about the Mars rovers. I think of those dry, orange, rocky landscapes - utterly empty. No birds, no insects, no life - total silence. I imagine standing in this place of stillness until another sound starts to drift up from the plains below. It’s the everyday sound of wheels crunching over gravel. It’s mundanity is profound in this place. Now the landscape flickers between the familiar and the strange as the sand and the rocks are superimposed over the dry Lowveld riverbeds closer to home. These imaginings make me desperately sad as well as in awe of what it is to be human and our lonely place in the universe. This oscillation between the familiar and the alien is central to what I am trying to achieve with these artefacts. I am interested in making intriguing objects that draw you in with the promise of clarity but that resists it at all costs.

Inspiration for these pieces come from two main sources. Once again I am talking about Driving Creek which was built by Barry Brickell who is a New Zealand national treasure and was an incredible potter, pioneer and railway fanatic. He built the potteries as well as a railway that runs into the hills so that he could dig out his clay and transport it back to his studio. Over the years as he and his fellow enthusiasts upgraded and extended the railway they populated the railside with strange ceramic creatures, vessels, ponds, cryptic markers and rusted bolts, gears and perplexing engineering offcuts. Driving Creek has slowly become an archeological phantasmagoria of imaginative musings and discarded railway wreckage. While I had previously been working in this area of puzzling machine parts, my sensory experience at DC provided a strong aesthetic framework for these particular pieces.

When Barry Brickell purchased the land at Driving Creek, the hills had been deforested, converted to cattle pastures and then abandoned. He used his railway to plant over 70 000 native endemic trees and shrubs and now the hills are reverted to pristine New Zealand forest. I became fixated on this conjunction of a human planted forest with the rusted relics of a carbon burning transportation system - two aspects that seem totally at odds with each other but which harmonise in such an interesting way. I was reminded of fossil diatoms which are microscopic mono cellular plankton that live in our rivers and oceans. They have a silica based exoskeleton and their shapes are truly fantastic, forcing us to revise what we think of as ‘natural’ shapes and forms. Some of them look like they could easily be the missing pieces of some mechanically geared machine.

So Driving Creek, diatoms, gears and rust. Familiar strangeness and objects that resist clarity. Ancient relics of lost civilisations and the sound of wheels turning over Martian gravel.